Campaign teams and adjacent organizations that support candidates, issues, and voters are wonders to the nerds like us who spend our time thinking about how teams work. They are built and torn down over the course of the election cycle. The folks who bring their talents work tirelessly together and then, win or lose, disband shortly after the election. Along the way, these teams - and the people who manage them - weather incredible stress.

Campaign work is a roller coaster ride for the nervous system. It is filled with unexpected turns that happen completely out of the scope and control of most of the folks working behind the scenes— we saw these turns over the last few months with Biden's departure from the race, and with the Democratic party enthusiastically coalescing around Kamala Harris. Deflation and a sense of impending doom have turned into energy and joy in the span of a few weeks. That wouldn't be happening without a lot of hard work and long nights from campaign staff working to shift the narrative and, along with it, our collective experience.

And while those good folks working to inform and energize us have their eyes on the prize of protecting democracy (no big deal), they’re also doing the intricate work of leading teams with the emotional intelligence this moment requires. They’re working to communicate effectively, to inspire and motivate, to navigate challenges, and to make decisions that consider the emotional well being of the folks around them.

In Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, Emily and Amelia Nagoski explore the concept of burnout and how it affects women in particular, who experience a unique confluence of stress and societal pressures. They explain stress vs. stressors:

Stressors = external events that trigger stress, like that boss with whom you just cannot get on the same page, or watching swings in poll numbers (even though we know better than to pay too much heed to poll data).

Stress = the physiological and emotional response to these stressors, like how you seem to be getting more headaches these days and you are finding yourself feeling really tired even after a good night of sleep (what’s that?).

Emily and Amelia Nagoski urge us to complete the stress cycle in order to alleviate stress. Completing the stress cycle means engaging in activities that will allow your body to process and release stress, like physical exercise, deep breathing, and positive social interactions.

Our coaching conversations with folks leading campaign and campaign-adjacent teams often center the tactical. These leaders carry a near-impossible responsibility to create and hold space for their teams to feel their feelings, and to care for themselves, while continuously delivering at a breakneck pace. We’ve been talking with these leaders about how they can help themselves and their teams complete the stress cycle as individuals and collectively. Here’s a roundup of some of the practices we’re seeing these leaders use to help their folks manage stress and connect. (Shoutout to them: They know who they are, and they rock!)

Name and See Feelings

It starts with feelings. Our capacity for feeling is the great uniter of our human experience, and yet it is often the one most feared. Feelings come in an immense range of shapes and sizes. In today’s world, it seems like negative feelings are at an all-time high, and managing those feelings can be even more challenging. Increasing your awareness of your own emotional state, acknowledging what you’re feeling and sharing that feeling out loud, is at the foundation of developing your emotional intelligence. Increasing emotional intelligence on a team creates space for individuals to have a human experience, to be connected to themselves and others, to provide an opportunity to regulate and co-regulate. Empathy and connection are critical building blocks for team and individual resilience.

Try starting a meeting with a moment for folks to settle in. If you’re gathering virtually, ask people to name how they’re feeling in the chat. Set a timer for two minutes. Encourage them to watch each other’s responses. Maybe name some out loud as participants type. And then: Do nothing. Sit in quiet together, witnessing each other. Close with a breath or two. Acknowledge that you see your people, and you see their feelings.

Use Check In / Check Out Rituals

When a 24-hour news cycle brings an endless cascade of news that feels both urgent and important, gathering your team first thing in the morning to check in, and again at the end of the day to check out, can be deeply centering.

Check ins allow members of your team to share their current status, feelings, obstacles — all of which promotes transparency and support. Check outs provide a space to reflect on the day’s achievements, anticipate challenges, and set intentions. This routine helps create space where folks feel heard, and can even open pathways for collaboration when folks are listening for where they can support each other.

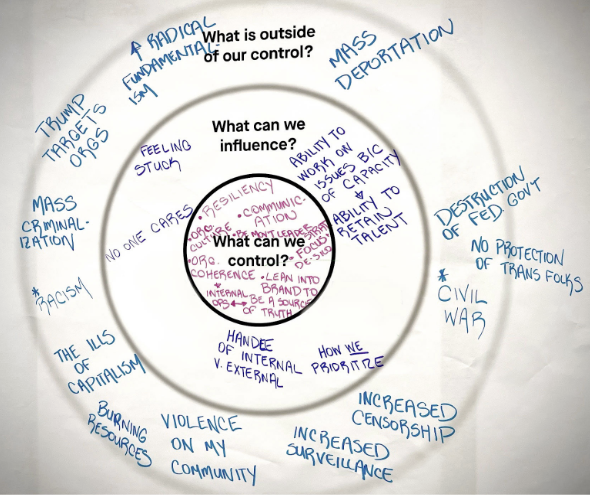

Dig Into Fears

More specifically than naming feelings, articulating fears and their deepest consequences goes straight after those most negative spaces. Creating opportunities for folks to engage with each other about their worst fears helps to normalize, and can help build perspective, ultimately (hopefully) paving the way for more of a sense of empowerment.

Ask your folks to think through their responses to the following prompts:

“I’m afraid of …”

“If my worst fears materialize, it will mean … is happening.”

Then allow for some time to share, to release, to build resonance across the group, to hold each other’s fears in focus in an effort to lighten the load. Take a few breaths together.

Invite Questions

Inviting your folks into opportunities explicitly designed for them to ask questions demystifies so much (namely power and authority) and promotes a culture of continuous learning and improvement. Having folks ask questions, ideally out in the open, can make space for innovation and collaboration in ways not possible when asking questions feels fraught.

You can work an invitation to ask questions into your check in / check out agenda, or into your weekly team meetings. Start by modeling questions that operate at multiple levels, and maybe even model both technical and tactical questions and more philosophical questions that require nuance and conversation. Keep track of these questions in a shared document, encourage folks to respond so that it comes to life, and continuously revisit the question round-up with opportunities to add more questions.

Go Outside and Move

In the first chapter of Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, the authors write: “Physical activity (literally any movement of your body) is what tells your brain you have successfully survived the threat and now your body is a safe place to live. Physical activity is the single most efficient strategy for completing the stress response cycle.”

If getting outside and moving your bodies is accessible to your team, moving with the group can tackle multiple strategies to complete the stress response cycle. Physical activity + positive social interactions = so many wins for the day. One of our current campaign team leaders encourages team hikes, and we have suggested that they schedule those hikes right on into the work week. Go outside if you can. Move if you can. We promise you’ll feel better.

Plan for Joy

Is it any wonder why your favorite standup’s latest routine feels extra funny right now? Or why you had an especially amazing time at that summer concert last weekend where you danced your ass off? Back to the Nagoski sisters: You were closing the stress cycle. Laughter and joy trigger the release of endorphins that make us feel happy and relaxed. So no, it’s no wonder.

Ask everyone on your team to identify one thing they’ll do today to experience joy. We’re looking for things like: I will blast music in my car and sing as loud as I can during my 20 minute ride home. I will put my phone in a drawer and play a round of Sleeping Queens with my 7-year-old before bedtime.

Better yet, plan for some shared joy. Get your team out for an afternoon at the park or the lake and bring some silly games. Go to a museum. Meet up for a great meal. And no matter what: Ban cell phones from these events. The world will not end if you don’t see your social media alerts, but you will have connected and (hopefully) relaxed together.

Need some help building practices to help your team complete the stress cycle? Go buy yourself a copy of Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle because it’s SO good, and then let’s have a conversation about scheduling a session to support your practice.